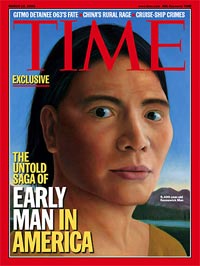

TIME MAGAZINE: THE FIRST AMERICANS

ArchaeologyWho Were The First Americans?

They may have been a lot like Kennewick Man, whose hotly disputed bones are helping rewrite our earliest history. An exclusive inside look

By MICHAEL D. LEMONICK, ANDREA DORFMAN

Mar. 13, 2006

It was clear from the moment Jim Chatters first saw the partial skeleton that no crime had been committed--none recent enough to be prosecutable, anyway. Chatters, a forensic anthropologist, had been called in by the coroner of Benton County, Wash., to consult on some bones found by two college students on the banks of the Columbia River, near the town of Kennewick. The bones were obviously old, and when the coroner asked for an opinion, Chatters' off-the-cuff guess, based on the skull's superficially Caucasoid features, was that they probably belonged to a settler from the late 1800s. • Then a CT scan revealed a stone spear point embedded in the skeleton's pelvis, so Chatters sent a bit of finger bone off to the University of California at Riverside for radiocarbon dating. When the results came back, it was clear that his estimate was dramatically off the mark. The bones weren't 100 or even 1,000 years old. They belonged to a man who had walked the banks of the Columbia more than 9,000 years ago.

In short, the remains that came to be known as Kennewick Man were almost twice as old as the celebrated Iceman discovered in 1991 in an Alpine glacier, and among the oldest and most complete skeletons ever found in the Americas. Plenty of archaeological sites date back that far, or nearly so, but scientists have found only about 50 skeletons of such antiquity, most of them fragmentary. Any new find can thus add crucial insight into the ongoing mystery of who first colonized the New World--the last corner of the globe to be populated by humans. Kennewick Man could cast some much needed light on the murky questions of when that epochal migration took place, where the first Americans originally came from and how they got here.

U.S. government researchers examined the bones, but it would take almost a decade for independent scientists to get a good look at the skeleton. Although it was found in the summer of 1996, the local Umatilla Indians and four other Columbia Basin tribes almost immediately claimed it as ancestral remains under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (see box), demanding that the skeleton be reburied without the desecration of scientific study. A group of researchers sued, starting a legal tug-of-war and negotiations that ended only last summer, with the scientists getting their first extensive access to the bones. And now, for the first time, we know the results of that examination.

WHAT THE BONES REVEALED

It was clearly worth the wait. The scientific team that examined the skeleton was led by forensic anthropologist Douglas Owsley of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History. He has worked with thousands of historic and prehistoric skeletons, including those of Jamestown colonists, Plains Indians and Civil War soldiers. He helped identify remains from the Branch Davidian compound in Texas, the 9/11 attack on the Pentagon and mass graves in Croatia.

In this case, Owsley and his team were able to nail down or make strong guesses about Kennewick Man's physical attributes. He stood about 5 ft. 9 in. tall and was fairly muscular. He was clearly right-handed: the bones of the right arm are markedly larger than those of the left. In fact, says Owsley, "the bones are so robust that they're bent," the result, he speculates, of muscles built up during a lifetime of hunting and spear fishing.

An examination of the joints showed that Kennewick Man had arthritis in the right elbow, both knees and several vertebrae but that it wasn't severe enough to be crippling. He had suffered plenty of trauma as well. "One rib was fractured and healed," says Owsley, "and there is a depression fracture on his forehead and a similar indentation on the left side of the head." None of those fractures were fatal, though, and neither was the spear jab. "The injury looks healed," says Owsley. "It wasn't a weeping abscess." Previous estimates had Kennewick Man's age as 45 to 55 when he died, but Owsley thinks he may have been as young as 38. Nothing in the bones reveals what caused his demise.

But that's just the beginning of an impressive catalog of information that the scientists have added to what was already known--all the more impressive given the limitations placed on the team by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which is responsible for the skeleton because the Corps has jurisdiction over the federal land on which it was found. The researchers had to do nearly all their work at the University of Washington's Burke Museum, where Kennewick Man has been housed in a locked room since 1998, under the watchful eyes of representatives of both the Corps and the museum, and according to a strict schedule that had to be submitted in advance. "We only had 10 days to do everything we wanted to do," says Owsley. "It was like a choreographed dance."

Perhaps the most remarkable discovery: Kennewick Man had been buried deliberately. By looking at concentrations of calcium carbonate left behind as underground water collected on the underside of the bones and then evaporated, scientists can tell that he was lying on his back with his feet rolled slightly outward and his arms at his side, the palms facing down--a position that could hardly have come about by accident. And there was no evidence that animal scavengers had been at the body.

The researchers could also tell that Kennewick Man had been buried parallel to the Columbia, with his left side toward the water: the bones were abraded on that side by water that eroded the bank and eventually dumped him out. It probably happened no more than six months before he was discovered, says team member Thomas Stafford, a research geochemist based in Lafayette, Colo. "It wouldn't have been as much as a year," he says. "The bones would have been more widely dispersed."

The deliberate burial makes it especially frustrating for scientists that the Corps in 1998 dumped hundreds of tons of boulders, dirt and sand on the discovery site--officially as part of a project to combat erosion along the Columbia River, although some scientists suspect it was also to avoid further conflict with the local tribes. Kennewick Man's actual burial pit had already been washed away by the time Stafford visited the site in December 1997, but a careful survey might have turned up artifacts that could have been buried with him. And if his was part of a larger burial plot, there's now no way for archaeologists to locate any contemporaries who might have been interred close by.

Still, the bones have more secrets to reveal. They were never fossilized, and a careful analysis of their carbon and nitrogen composition, yet to be performed, should reveal plenty about Kennewick Man's diet. Says Stafford: "We can tell if he ate nothing but plants, predominantly meat or a mixture of the two." The researchers may be able to determine whether he preferred meat or fish. It's even possible that DNA could be extracted and analyzed someday.

While the Corps insisted that most of the bones remain in the museum, it allowed the researchers to send the skull fragments and the right hip, along with its embedded spear point, to a lab in Lincolnshire, Ill., for ultrahigh-resolution CT scanning. The process produced virtual slices just 0.39 mm (about 0.02 in.) thick--"much more detailed than the ones made of King Tut's mummy," says Owsley. The slices were then digitally recombined into 3-D computer images that were used to make exact copies out of plastic. The replica of the skull has already enabled scientists to clear up a popular misconception that dates back to the initial reports of the discovery.

WAS KENNEWICK MAN CAUCASIAN?

Thanks to Chatters' mention of Caucasoid features back in 1996, the myth that Kennewick Man might have been European never quite died out. The reconstructed skull confirms that he was not--and Chatters never seriously thought otherwise. "I tried my damnedest to curtail that business about Caucasians in America early," he says. "I'm not talking about today's Caucasians. I'm saying they had 'Caucasoid-like' characteristics. There's a big difference." Says Owsley: "[Kennewick Man] is not North American looking, and he's not tied in to Siberian or Northeast Asian populations. He looks more Polynesian or more like the Ainu [an ethnic group that is now found only in northern Japan but in prehistoric times lived throughout coastal areas of eastern Asia] or southern Asians."

That assessment will be tested more rigorously when researchers compare Kennewick Man's skull with databases of several thousand other skulls, both modern and ancient. But provisionally, at least, the evidence fits in with a revolutionary new picture that over the past decade has utterly transformed anthropologists' long-held theories about the colonization of the Americas.

WHO REALLY DISCOVERED AMERICA?

The conventional answer to that question dates to the early 1930s, when stone projectile points that were nearly identical began to turn up at sites across the American Southwest. They suggested a single cultural tradition that was christened Clovis, after an 11,000-year-old-plus site near Clovis, N.M. And because no older sites were known to exist in the Americas, scientists assumed that the Clovis people were the first to arrive. They came, according to the theory, no more than 12,000 years B.P. (before the present), walking across the dry land that connected modern Russia and Alaska at the end of the last ice age, when sea level was hundreds of feet lower than it is today. From there, the earliest immigrants would have made their way south through an ice-free corridor that geologists know cut through what are now the Yukon and Mackenzie river valleys, then along the eastern flank of the Canadian Rockies to the continental U.S. and on to Latin America.

That's the story textbooks told for decades--and it's almost certainly wrong. The first cracks in the theory began appearing in the 1980s, when archaeologists discovered sites in both North and South America that seemed to predate the Clovis culture. Then came genetic and linguistic analyses suggesting that Asian and Native American populations diverged not 12,000 years ago but closer to 30,000 years ago. Studies of ancient skulls hinted that the earliest Americans in South America had different ancestors from those in the North. Finally, it began to be clear that artifacts from Northeast Asia dating from just before the Clovis period and South American artifacts of comparable age didn't have much in common with Clovis artifacts.

Those discoveries led to all sorts of competing theories, but few archaeologists or anthropologists took them seriously until 1997. In that year, a blue-ribbon panel of researchers took a hard look at evidence presented by Tom Dillehay, then at the University of Kentucky, from a site he had been excavating in Monte Verde, Chile. After years of skepticism, the panel finally affirmed his claim that the site proved humans had lived there 12,500 years ago. "Monte Verde was the turning point," says David Meltzer, a professor of prehistory at Southern Methodist University in Dallas who was on the panel. "It broke the Clovis barrier."

Why? Because if people were living in southern Chile 12,500 years ago, they must have crossed over from Asia considerably earlier, and that means they couldn't have used the ice-free inland corridor; it didn't yet exist. "You could walk to Fairbanks," says Meltzer. "It was getting south from Fairbanks that was a problem." Instead, many scientists now believe, the earliest Americans traveled down the Pacific coast--possibly even using boats. The idea has been around for a long time, but few took it seriously before Monte Verde.

One who did was Jon Erlandson, an archaeologist at the University of Oregon, whose work in Daisy Cave on San Miguel Island in California's Channel Island chain uncovered stone cutting tools that date to about 10,500 years B.P., proving that people were traveling across the water at least that early. More recently, researchers at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History redated the skeletal remains of an individual dubbed Arlington Springs Woman, found on another of the Channel Islands, pushing her age back to about 11,000 years B.P. Farther south, on Cedros Island off the coast of Baja California, U.C. at Riverside researchers found shell middens--heaps of kitchen waste, essentially--and other materials that date back to the same period as Daisy Cave. Down in the Andes, researchers have found coastal sites with shell middens dating to about 10,500 years B.P.

And in a discovery that offers a sharp contrast to the political hoopla over Kennewick Man, scientists and local Tlingit and Haida tribes cooperated so that researchers could study skeletal remains found in On Your Knees Cave on Prince of Wales Island in southern Alaska. "There's no controversy," says Erlandson, who has investigated cave sites in the same region. "It hardly ever hits the papers." Of about the same vintage as Kennewick Man and found at around the same time, the Alaskan bones, along with other artifacts in the area, lend strong support to the coastal-migration theory. "Isotopic analysis of the human remains," says James Dixon, the University of Colorado at Boulder anthropologist who found them, "demonstrates that the individual--a young male in his early 20s--was raised primarily on a diet of seafood."

CRUISING DOWN THE KELP HIGHWAY

Erlandson has found one more line of evidence that supports the migration theory. While working with a group of marine ecologists, he was startled to learn that there were nearly continuous kelp forests growing just offshore all the way from Japan in the western Pacific to Alaska and down the West Coast to Baja California, then (with a gap in the tropics) off the coast of South America. In a paper presented three weeks ago, he outlined the potential importance to the earliest Americans of what he calls the "kelp highway."

"Most of the early sites on the west coast are found adjacent to kelp forests, even in Peru and Chile," he says. "The thing about kelp forests is they're extremely productive." They not only provide abundant food, from fish, shellfish, seals and otters that thrive there, but they also reduce wave energy, making it easier to navigate offshore waters. By contrast, the inland route along the ice-free corridor would have presented travelers with enormous ecological variability, forcing them to adapt to new conditions and food sources as they traveled.

Unfortunately, the strongest evidence for the coastal theory lies offshore, where ancient settlements would have been submerged by rising seas over the past 10,000 years or so. "Artifacts have been found on the continental shelves," says Dixon, "so I'm quite confident there's material out there." But you need submersible craft to search, and, he says, that type of research is a very hard sell to the people who own and operate that kind of equipment. "The maritime community is interested in shipwrecks and treasures. A little bit of charcoal and some rocks on the ocean floor is not very exciting to them."

MULTIPLE MIGRATIONS

Even if the earliest Americans traveled down the coast, that doesn't mean they couldn't have come through the interior as well. Could there have been multiple waves of migration along a variety of different routes? One way scientists have tried to get a handle on that question is through genetics. Their studies have focused on two different types of evidence extracted from the cells of modern Native Americans: mitochondrial DNA, which resides outside the nuclei of cells and is passed down only through the mother; and the Y chromosome, which is passed down only from father to son. Since DNA changes subtly over the generations, it serves as a sort of molecular clock, and by measuring differences between populations, you can gauge when they were part of the same group.

Or at least you can try. Those molecular clocks are still rather crude. "The mitochondrial DNA signals a migration up to 30,000 years ago," says research geneticist Michael Hammer of the University of Arizona. "But the Y suggests that it occurred within the last 20,000 years." That's quite a discrepancy. Nevertheless, Hammer believes that the evidence is consistent with a single pulse of migration.

Theodore Schurr, director of the University of Pennsylvania's Laboratory of Molecular Anthropology, thinks there could have been many migrations. "It looks like there may have been one primary migration, but certain genetic markers are more prevalent in North America than in South America," Schurr explains, suggesting secondary waves. At this point, there's no definitive proof of either idea, but the evidence and logic lean toward multiple migrations. "If one migration made it over," Dillehay, now at Vanderbilt University, asks rhetorically, "why not more?"

OUT OF SIBERIA?

Genetics also points to an original homeland for the first Americans--or at least it does to some researchers. "Skeletal remains are very rare, but the genetic evidence suggests they came from the Lake Baikal region" of Russia, says anthropologist Ted Goebel of the University of Nevada at Reno, who has worked extensively in that part of southern Siberia. "There is a rich archaeological record there," he says, "beginning about 40,000 years ago." Based on what he and Russian colleagues have found, Goebel speculates that there were two northward migratory pulses, the first between 28,000 and 20,000 years ago and a second sometime after 17,000 years ago. "Either one could have led to the peopling of the Americas," he says.

Like just about everything else about the first Americans, however, this idea is open to vigorous debate. The Clovis-first theory is pretty much dead, and the case for coastal migration appears to be getting stronger all the time. But in a field so recently liberated from a dogma that has kept it in an intellectual straitjacket since Franklin Roosevelt was President, all sorts of ideas are suddenly on the table. Could prehistoric Asians, for example, have sailed directly across the Pacific to South America? That may seem far-fetched, but scientists know that people sailing from Southeast Asia reached Australia some 60,000 years ago. And in 1947 the explorer Thor Heyerdahl showed it was possible to travel across the Pacific by raft in the other direction.

At least a couple of archaeologists, including Dennis Stanford of the Smithsonian, even go so far as to suggest that the earliest Americans came from Europe, not Asia, pointing to similarities between Clovis spear points and blades from France and Spain dating to between 20,500 and 17,000 years B.P. (Meltzer, Goebel and another colleague recently published a paper calling this an "outrageous hypothesis," but Dillehay thinks it's possible.)

All this speculation is spurring a new burst of scholarship about locations all over the Americas. The Topper site in South Carolina, Cactus Hill in Virginia, Pennsylvania's Meadowcroft, the Taima-Taima waterhole in Venezuela and several rock shelters in Brazil all seem to be pre-Clovis. Dillehay has found several sites in Peru that date to between 10,000 and 11,000 years B.P. but have no apparent links to the Clovis culture. "They show a great deal of diversity," he says, "suggesting different early sources of cultural development in the highlands and along the coast."

It's only by studying those sites in detail and continuing to search for more evidence on land and offshore that these questions can be fully answered. And as always, the most valuable evidence will be the earthly remains of the ancient people themselves. In one 10-day session, Kennewick Man has added immeasurably to anthropologists' store of knowledge, and the next round of study is already under way. If scientists treat those bones with respect and Native American groups acknowledge the importance of unlocking their secrets, the mystery of how and when the New World was populated may finally be laid to rest.

Coming To America

For decades, scientists thought the New World was populated by migrants from Asia who wandered down the center of the continent about 12,000 years ago. New discoveries are pushing that theory out to sea. Three views on how humans populated the Americas

- COASTAL Recent finds at Daisy Cave, Calif., and Monte Verde, Chile, point to bands of people moving down the Pacific coast of North and South America much earlier, perhaps 30,000 years ago

- OVERLAND Discoveries at Clovis, N.M., led to the theory that a single human culture moved into the Americas down the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains about 12,000 years ago

- ATLANTIC Artifacts found in South Carolina have led some archaeologists to speculate that early migrants might have arrived on the East Coast from Europe, although the evidence remains in dispute Select archaeological sites*

- Other artifacts found Ushki Lake RUSSIA 11,000 B.P. • Human remains found On Your Knees Cave ALASKA 9,818 B.P. • Human remains found Kennewick WASH. 9,400 B.P.

- Other artifacts found Daisy Cave CALIF. 10,500 B.P.

- Other artifacts found Cedros Island MEXICO 11,000 B.P.

- Other artifacts found Folsom N.M. 10,490 B.P.

- Other artifacts found Clovis N.M. 11,200 B.P. • Dates in dispute Meadowcroft PA. 14,250 B.P. • Dates in dispute Cactus Hill VA. 15,070 B.P. • Dates in dispute Topper S.C. 15,200 B.P. • Dates in dispute Taima-Taima VENEZUELA 13,000 B.P.

- Other artifacts found Pedra Furada BRAZIL 47,000 B.P.

- Other artifacts found Lapa do Boquete BRAZIL Up to 12,070 B.P.

- Other artifacts found Tibit COLOMBIA 11,740 B.P.

- Other artifacts found Quebrada Jaguay PERU 10,500 B.P.

- Other artifacts found Monte Verde CHILE 12,500 B.P.

- Human remains found Palli Aike CHILE 8,640 B.P.

Tools in the search ARCHAEOLOGY Skeletons like Kennewick Man are rare. More often scientists study and date other indications of human activity -- remains of butchered animals, stone tools, spear points or even bits of burned charcoal. Unfortunately, such artifacts may never be found along coastal migration routes -- they're now under water

GENETICS Scientists use markers in DNA samples from indigenous peoples in North and South America to figure out when populations diverged from each other. DNA comparisons suggest the first Americans may have diverged from groups in the Lake Baikal area of what is now Russia as early as 26,000 years ago

LINGUISTICS By studying native words and grammar, scientists can establish links and infer the amount of time required for different languages to evolve from a common origin. As of 1492, there were an estimated 1,000 languages in the Americas that may have developed from the original migrants

Migration milestones

- 30,000 B.P.* Beginning of last North American ice age. Mitochondrial-DNA studies indicate the earliest possible migration

- 25,000 Approximate opening of Bering land bridge between Asia and North America

- 20,000 Earliest migration date, according to Y-chromosome studies • 15,000 Evidence of humans in South America Glacial melting floods Bering land bridge • 10,000 End of last ice age in North America Kennewick Man lives in Pacific Northwest • 5,000 Dawn of Central American cultures such as Olmec and Maya • Present

*Dates are in radiocarbon years "before the present," a scientific standard meaning "before 1950"

—With reporting by With reporting by Dan Cray/Los Angeles

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home